DECEMBER 1989 – THE ARMY AND THE REVOLUTION

- angelogeorge988

- Jan 1

- 18 min read

Updated: Jan 13

Anno Domini 1989. Romania (Eastern Europe) had lived for forty-five years under the communist yoke, twenty-five of them under Ceaușescu’s personal dictatorship. The country had become the perfect image of a totalitarian disaster: nothing worked as it should anymore.

Romania in Ruins

The industry primarily produced machine tools and various types of heavy equipment, of mediocre quality at best. Some of these were destined for Russia (then called the Soviet Union) and the other communist countries of Eastern Europe. They were purchased through a barter system, exchanged for other products just as useless and just as defective. The rest were sold to countries in Africa, in return for payments that would never be made. Agriculture told a similar story. According to official propaganda, Romania’s agricultural output was three times that of France. In reality, the country produced at most 10% of France’s output—and that figure comes from an optimistic estimate.

The Inefficient “Organs”

The Organele were the repressive apparatus of Romania’s communist regime—necessary, even essential, to keeping Ceaușescu and the Communist Party in power. These included the 'Militia', officially meant to function as the police, but in practice mainly concerned with punishing those who inconvenienced the smaller or larger bosses of the Communist Party; and the 'Securitate', Romania’s equivalent of the KGB or the Gestapo. Their role was to crush any form of opposition, to destroy it before it could even take shape. Yet by September 1989, they too were severely affected by the regime’s senility and obsolescence. They were eaten to the bone by the cancer of corruption, clientelism, nepotism, and incompetence. Even so, they still retained the ability to instil deep fear in the population—a boundless terror in those who might have considered opposing the regime. But this fear was largely a myth, a legend sustained by what the Securitate had once been capable of doing. The proof? Us—myself, Angelo, and George, my friend and partner in violating the regime’s so-called “communist values.” We were nineteen years old, rockers and karate practitioners—the most dangerous categories imaginable for Ceaușescu’s regime. We embodied everything the communist authorities hated and feared most; we were, or should have been, seen and treated as their mortal enemies.

No Repression Against Us

Thirty years earlier, we would have been shot. Or, at best, sent to forced labour camps, where we would have worked ourselves to death through sheer physical exhaustion. Twenty years earlier, we would have been thrown into prison and forgotten there. Ten years before that, we would have been committed to a psychiatric hospital, to the ward for “the most dangerous lunatics.” But in 1989, the worst that could have happened to us was a thorough beating in a Militia station—if they managed to get their hands on us, which happened very rarely.

What the hell were we doing here?

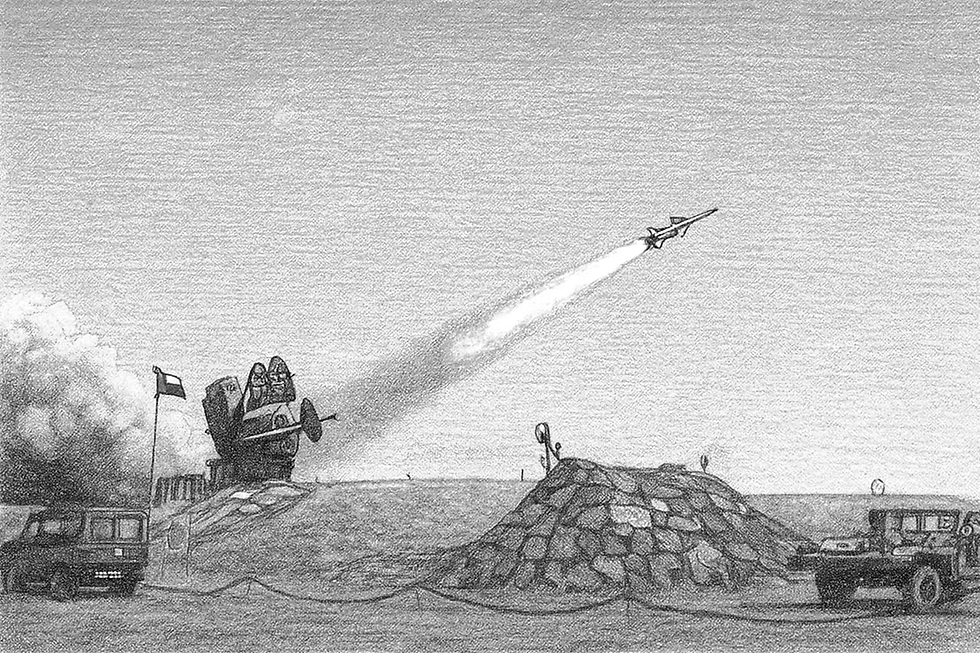

Against this backdrop of absolute collapse, in September 1989, we were called up for compulsory military service. Another sign of the regime’s stupidity: we were assigned to anti-aircraft defence units equipped with Volhov M3 missiles—the most modern and effective weapons of the time, the equivalent of today’s Patriot batteries. So we, the “enemies of the people”—of the “communist people,” of course—were sent to the most elite units of the Romanian army. How was this possible? What were the army bureaucrats thinking? Most likely, the aptitude tests during conscription revealed our exceptional abilities—the very ones we were to demonstrate throughout our military service.

In Key Positions

Moreover, once we arrived at the unit to which we had been assigned, we were immediately placed in key positions. I, Angelo, was designated as a “launcher”: my task was to prepare the missile and bring it to “ready-to-fire” status. George, my friend, was responsible for the “plotting board”: he calculated the target’s possible trajectories and determined the optimal moment to launch the missile to intercept it—a task performed today by computers, which did not exist at the time. Naturally, we pushed ourselves relentlessly to achieve “operational” status—that is, combat-ready. It was necessary if we were to accomplish our objectives.

What Did We Want?

I, Angelo, wanted to stay in the army and become a fighter pilot. My inseparable friend, George, decided to follow me on this adventure—madness, really—though he chose air defence, since that was the branch in which he was serving. It gave rise to an excellent running joke between us: one of us would fly an aircraft, the other would train to shoot them down. We also had more pragmatic reasons for this choice. First and foremost, it allowed us to escape the nightmare career toward which our beloved high-school teachers had been steering us: becoming miners in the Jiu Valley, the most wretched jobs in Romania at the time (a story told in 'Communist High School Chronicle: Under Ohm's Dictatorship'). At the same time, life in the army became easier, as officers treated us as potential future colleagues. All of this, combined with intensive military training—justified by the need to become “operational” as quickly as possible—helped us cope more easily with the separation.

We Are Separated

Unfortunately, we were not assigned to the same military unit. George was sent to Adâncata, a village near Ploiești, some 70 kilometres from Bucharest, the capital of the country. I, Angelo, on the other hand, was dispatched to Hațeg, roughly 500 kilometres away, even though conscripts were normally assigned close to home. And so we were separated, after having formed a true “Dream Team” during our four years of high school. Under different circumstances, we might have believed it was deliberate—that someone had decided to split us up, informed by our teachers of how we had mocked “communist values” throughout high school. Nothing of the sort. It was merely another symptom of the advanced state of decay Romania was in at the time. Proof: no fewer than twenty recruits from Bucharest were sent to Hațeg to do their military service there.

University Graduates

One might have expected the general commanding the unit to correct the mistake immediately. Not at all. He let out a howl of satisfaction when he saw me, Angelo, and my other 19 comrades from Bucharest: “My God, twenty capitalists!”—that is, people from the capital. At the time, coming from Bucharest made us seem like university graduates compared to recruits from other regions of the country. We were almost immediately sent to “school” to become operational as fast as possible. I must say we lived up to his expectations, reaching the required level in just a few weeks. After a demonstration in front of him, the general exclaimed happily: “At the next live-fire exercises, we’ll get the highest scores—we’ll crush the other regiments.” But life—or rather, army bureaucrats—had other plans. His dream was never fulfilled.

To the Guns, Brothers!

Unfortunately, six weeks later, those same bureaucrats decided to “correct” the error. We were already fully operational and proficient in handling the Volhov surface-to-air missile battery—the most advanced military technology of the time—when the order came: “Move out!” We were put on a train and sent to join a unit in the village of Bărăganu, about 120 kilometres from Bucharest, where we should have been assigned from the start. “The error has been corrected,” the army bureaucrats probably told themselves. As was so often the case under communism, the remedy proved worse than the disease. We were transferred to an anti-aircraft gun unit—weapons that had indeed been very modern… during the Second World War.

“Sacrilege!”

That was the word we all shouted in unison when we learned what military technology we were now expected to specialise in—and it was the mildest expression we used, the others being unprintable. The commander’s reaction was unequivocal: we began our service in his unit with a visit to the brig—military arrest. As it turned out, this worked out perfectly for the “major manoeuvres” my comrades undertook to avoid humiliation: retraining on “guns” after “missiles.” The PCR system - 'pile, cunoștințe și relații' (connections, acquaintances, and influence) - was swiftly activated, supplemented by a generous dose of bribes, and the problem was solved. Positions such as “briefcase carrier,” orderly, or courier were quickly invented for them, and they spent the rest of their service “in the warm”—that is, far from any field, agricultural or training-related. That was not my fate. I, Angelo, was deemed the instigator of this mini-revolt.

The Future Looked Bright

As a result, I alternated days in military arrest for various acts of insubordination with training to become an elite marksman. I achieved the best shooting results at the firing range. At one point, I was even temporarily transferred to another unit to train soldiers there. Fortunately for me, it was an aviation unit, and I made the connections necessary to apply to the Aviation School at Bobocu town. And George? During all this time, he stayed put and continued to progress, becoming the lead “plotting-board operator” in his unit. Everything pointed toward our replacing the dreaded career of “miner in the Jiu Valley” with that of officers in the Romanian Army. Then the Revolution came, and our lives took an unexpected turn. Worlds and careers we had only dreamed of suddenly became possible—accessible.

Do Not Fire on the Protesters

I, Angelo, remember that moment very clearly—the moment I understood that my life was about to change radically. Together with twenty-nine other comrades, I was part of the “intervention group,” those meant to be the first into combat in the event of an enemy attack on our unit. But on the morning of 22 December, we were waiting to be sent to Bucharest to protect Ceaușescu and his regime. The order had already been issued by Ceaușescu’s people, but our commanders were waiting for confirmation from the army leadership. The group commander, a lieutenant, was in the command centre, while we were in the unit’s armoury, equipping ourselves. With us was his deputy, a young non-commissioned officer who listened to Radio Free Europe every day. As we armed ourselves, he informed us of what was happening across the country and gave us a simple, decisive order: “Do not fire on the demonstrators—on the people.”

“Shoot the Securitate!”

Instead, he told us—indeed, he ordered us—to shoot those who might fire on the demonstrators and those who would give such orders. The Securitate, in other words. We were to stand with the people, with the protesters, and protect them. My comrades agreed with him in principle: among the demonstrators, there could well be members of their own families or close friends. Yet they were paralysed by fear—fear of the regime and of the Securitate. I no longer had that fear. Shouting “KIAI”—the battle cry of a martial arts practitioner - and brandishing my fully loaded submachine gun, I answered him: “This is an order I will carry out with the greatest pleasure, Sergeant. I have many scores to settle with them.”

“You’re right, Iris!”

Hearing this, my comrades burst into nervous but liberating laughter. Waving their Kalashnikovs in the air, they shouted in unison, “Down with the Dictator!”, laughing and crying at the same time. One by one, they embraced me, saying, “We know you’re right, Iris,” and “Costinești demands revenge.” “Iris” was my nickname in the army. My comrades had given it to me after the heavy rock band IRIS, of which I was an absolute fan. I had taught them the lyrics to all their songs by singing them—constantly—during every break, every moment of rest. My performances were disastrous; I had no voice whatsoever. But I sang—rather, I howled—with such soul and passion that they actually enjoyed listening. And what was “Costinești” about? A year before the army, George and I had gone there to attend the Rock Galas organised at the resort. Unfortunately, we were caught and beaten by the Militia, and the concert was cancelled (a story told in Freedom and the Baton: The First Chronicle of the Rock Generation).

No Order

But that order was never given. It could no longer be given. At the same time, soldiers deployed on the streets of Bucharest and other major cities were switching sides, joining those who were demonstrating against Ceaușescu. Shortly thereafter, the dictator fled, and his regime collapsed. With it, the communism imposed in 1945 by Russian tanks and bayonets was swept away, thrown onto the rubbish heap of history. Another dark page in Romania’s past was about to be turned—definitively, we hoped. And it had all begun a few days earlier, in Timișoara. Even we, locked inside our barracks, understood that Romania had begun its march toward freedom… on a December evening in 1989, in Timișoara.

The Spark

It is worth remembering that at the time, Timișoara was Romania’s second-largest city after the capital, Bucharest, and also the most Western in character. It was an important university and industrial centre. It is often said that great explosions begin with a spark. In December 1989, that spark was struck in Timișoara. At first, it was small, barely visible, but it would soon grow into a magnificent bonfire: the revolution against the dictator Ceaușescu and his communist regime. The trigger was something entirely mundane by the standards of Romania at the time: the decision to forcibly transfer Pastor László Tőkés. A decision taken by no one quite knows who, and for reasons no one ever clearly explained. The pastor refused to comply and called on his parishioners to support him. But in Romania, then, claiming the right to remain in one’s own home was tantamount to claiming freedom for all. On the evening of 15 December, the small group gathered in front of his house was quickly dispersed by the Militia.

The Flame of the Revolution Is Lit

The next day, however, his supporters returned in even greater numbers, more determined than ever. Appalling living conditions—marked by an acute shortage of almost everything required for a decent existence—had pushed them to the limit. They had nothing left to lose but their lives, and many felt that a life lived under such conditions was scarcely worth living at all. This time, the Militia’s riot-control units were deployed. Yet they were equipped only with shields, as shortages affected everyone; no surprise there. Agents of the communist secret police—the Securitate—were present as well, of course. Both the “investigators,” dressed in suits in a ridiculous attempt to imitate FBI agents, and the “enforcers,” the thugs—the “gorillas”—in KGB- or Gestapo-style leather coats. In reality, the coats were imitation leather, for they themselves were nothing more than a poor imitation of the real thing. They looked impressive, but only on the surface. In truth, they were poorly trained, led by idiots, and utterly unprepared to face people who were no longer afraid of anything. What was supposed to be a routine manhunt turned into a chaotic confrontation—a full-blown brawl. In the end, the demonstrators were beaten back and dispersed, but the outcome was bitter: only a handful were arrested. The rest escaped. And they were ordinary people, driven to desperation by life under Ceaușescu’s regime. After being severely beaten, those detained were released—but not before being threatened with “serious consequences” if they did not calm down.

The Collapse of the “Securitate” Myth

And they did not stop. News of the confrontation with the Militia and Securitate, the small number of people actually arrested, and the relatively minor consequences suffered by the demonstrators spread through the city like wildfire. The myth that the “Securitate” could arrest and make anyone opposing Ceaușescu and his regime disappear was shattered. This legend, this fear of the Securitate’s omnipotence, was what had allowed Ceaușescu to stay in power. Everything turned to ash and dust when the demonstrators of 15 and 16 December returned home largely unharmed. The people discovered that the feared Securitate had become a pathetic paper tiger—a pitiful shadow of the once all-powerful institution. Consequently, on 17 December, groups of demonstrators, ranging from a few dozen to several hundred, began to roam the city streets, waving symbols of their own making.

Symbols of the Revolution

The pastor Tőkés’ faithful followers had made up most of the crowd the day before. By 17 December, they were only a small minority among the demonstrators. The majority were young: high school students skipping communist political education classes, university students, rockers, karate practitioners, “ultras,” and even petty traders. Their interests varied, sometimes even clashing. Yet they were united by a fierce hatred of Ceaușescu and his inhuman communist regime. And, of course, they created their own symbols—the symbols of the Revolution: the holed flag and the song “Deșteaptă-te, române!” (Wake-up, Romanian!), similar to the anti-fascist resistance song adopted in Anglo-Saxon protest culture called “Bella Ciao”. The flag was still Romania’s tricolor, but with a hole in the middle where the emblem of Ceaușescu’s communist regime had been cut out. “Deșteaptă-te, române!” had been written a century earlier, but it had been banned by the communists. You can guess why. Heard for the first time in public on the streets of Timișoara after forty-five years of communism, it would later become Romania’s official national anthem. The scale of the movement, the number of demonstrators, and their determination shocked the communist authorities. The army was called in to save the day.

Gunfire… Powerless

It was a stark acknowledgment of their impotence; they officially admitted that the omnipotence of the Securitate now belonged to the past. And this only encouraged the people of Timișoara to continue and intensify their protests, despite hundreds of soldiers and dozens of armoured vehicles deployed across the city streets. These were not special forces—they existed only on paper. They were not even professional soldiers. They were simply recruits, eighteen or nineteen years old, given at best a cursory military training. Several times, usually at nightfall, they fired on the demonstrators—out of fear, stupidity, or, most often, at the orders of Securitate agents. The demonstrators would flee for cover, only to regroup elsewhere. One particularly brutal scene occurred when people sought refuge in the city’s cathedral, hoping for divine protection and the respect due to a sacred place. They were shot on the church steps. The communist authorities hated religion and God alike, behaving far worse than the non-believers of the past. The Ottomans, who were Muslim and had occupied Romanian territories for centuries, had shown far more respect for churches than the communists ever did.

The Soldiers Withdraw

On 18 December, the troops opened fire on the demonstrators again—dozens more killed, hundreds wounded. But this massacre did not frighten the people; it only strengthened their resolve. One can imagine them thinking: “Better dead than a communist. Death is preferable to a life in Ceaușescu’s miserable communist world.” And so even more people took to the streets than before. Increasing numbers from all social classes joined the protests. Workers began leaving their jobs to go home, but some never made it home, instead swelling the ranks of the demonstrators. And now they were shouting:

“We are not going home—the dead won’t let us!”

The communist authorities tried a diversion, accusing the protesters of looting. A ridiculous claim: loot what? The dust in the Ceaușescu-era stores, emptier than outer space (see: Scarce Food, A Guide to Survive Communism)? Meanwhile, discontent was growing among the soldiers deployed in the streets. Eventually, they were pulled back into the barracks, out of fear that they might join the demonstrators.

Timișoara, a Free City

By 19 December, the city was virtually emptied of law enforcement. Militia, Securitate, Army—no one remained on the streets. The demonstrators, growing in number by the hour, roamed freely and occupied the city’s main squares. In the industrial districts, workers declared a general strike as early as the morning. Their demands were radical: the dictator must go, the regime must be overthrown, and those who had fired on the protesters—or given the orders—must be severely punished. The communist authorities’ attempts to persuade them to back down were futile, and negotiations quickly stalled. By the next day, 20 December, workers joined the demonstrators en masse. Together, they stormed official buildings. Portraits of the dictator, emblems, and symbols of his communist regime were thrown into the trash or destroyed outright. Local authorities, emerging from among the protesters, began exercising power independent of Ceaușescu’s command in Bucharest. From that moment, Timișoara had become a city free from the dictator and communism.

“The Genius from the Carpathians”: Nonsense on a Conveyor Belt

Immediately, by Ceaușescu’s order, Timișoara was placed under quarantine; all connections with the rest of the country were cut: no trains, no buses, telephone communications severed. Total lockdown. Why? So that the rest of the country would not learn what was happening there. A futile effort—Radio Free Europe and other stations, even Bulgarian or Hungarian, had already spread the news across Romania. Then the dictator made a lightning visit to Iran to meet his friend, Ayatollah Khomeini, offering money and industrial and food products in exchange for troops to crush the uprising in Timișoara. The Iranians refused, on Gorbachev’s orders—he had already “sold” Eastern Communist Europe to the Americans in a desperate attempt to save the Russian Empire (then known as the Soviet Union). Returning empty-handed, Ceaușescu called, on 21 December, a massive pro-regime demonstration in Bucharest. A fatal mistake: the crowd in front of him was a powder keg waiting for a spark.

The Spark

Around 10 a.m., that spark appeared in the form of firecrackers exploding in the crowd. Within minutes, communist flags and placards in honour of Ceaușescu vanished. The dictator tried to regain control, promising more money. “Give them another hundred, Nicu,” whispered his wife. Useless. Everyone had money; what was lacking was food, electricity, gas—practically everything. His speech ended abruptly when the demonstrators began shouting “Timișoara!” and “Down with the dictator!” With his speech cut short, the live broadcast of the demonstration on television was also stopped. It was already too late: the entire country understood that something resembling a revolution was underway—even though people had not seen firsthand how a demonstration organized in support of Ceaușescu and his repression of Timișoara had turned into an anti-regime uprising. The central point: University Square, destined to become a symbol for Romanians, much like the Bastille for the French.

University Square

Situated in the heart of Bucharest at the intersection of several major boulevards, bordered by a green space in front of the National Theatre, University Square quickly became the epicenter of protest. Some who had left Ceaușescu’s rally came here to protest against him and his regime. They occupied the square, the streets, the green space, and the surrounding areas. Passersby, students, and people from all social strata joined them. Reinforcements arrived in the form of rockers from “Grădinița,” a terrace-bar in Piața Romană that served as their informal headquarters. They alerted others, who abandoned whatever they were doing and rushed to join them in growing numbers. These rockers were likely the first to chant “Down with communism!”, a slogan soon echoed by the crowd. It was the first time such words were shouted in Bucharest—and here, at University Square, it happened. From then on, the square became a symbol not only of resistance against Ceaușescu but also against communism itself. The regime’s anti-riot forces, equipped with shields, intervened—but untrained and poorly led, they were powerless against the determined demonstrators, many of whom were martial arts practitioners, like the rockers. The army was called in to assist, as it had been in Timișoara.

The Army’s Response

The head of the Romanian Army, General Victor Atanasie Stănculescu, suddenly fell ill and was hospitalized for a knee fracture. One day after Ceaușescu’s fall, he discovered he had lost nothing and resumed his position under the new regime. In this capacity, he participated in the decision to execute the dictator on Christmas Day. Later, as a reward, he became Minister of Defense. George’s unit commander issued the following order: “Soldiers, we remain on standby to see how events unfold, and we will align with whoever wins.” An opportunistic stance, of course, but showing a certain… prudence. Unfortunately, other unit commanders did not follow this approach and executed orders from the party apparatus of Ceaușescu’s regime, sending troops against the demonstrators. Dozens of armored vehicles, hundreds of soldiers. By nightfall, on the orders of Securitate agents, they attacked protesters with their vehicles, converted into bulldozers. They also opened fire on anyone building barricades or simply seeking shelter. Hundreds were injured, and dozens killed. Among them: him.

The Sacrifice of a Rocker

His name: Mihai Laurențiu Gâtlan. He was one of our closest friends, the first to introduce us to what it meant to be a Rocker, a metal fan. This happened several years earlier, when we attended an IRIS concert. He taught us the “Creed” of a Rocker’s life and the guiding “Words” (a story recounted in Libertatea și bastonul: the first chronicle of the rock generation). Courage and Unity: he and his friends, all Rockers, came out to protest against the Dictator and his murderous communist regime on 21 December in University Square. Some of them were injured. He died with Honor for Freedom. A commemorative plaque, Glory, was erected at the place where Ceaușescu’s forces killed him (details of his death are available here: About Mihai Gâtlan | fumg.org). His sacrifice, like that of many others, must not be forgotten. Nor should we forget those arrested and beaten in Militia and Securitate stations during the night of 21–22 December 1989.

Bucharest Rises Up

Fortunately, many demonstrators managed to escape the gunfire and repression, which reached its peak around midnight, bringing the protest to an end. They did not hide out of fear of the regime. They were not cowards. They did not yield to fear. On the contrary, they began moving through the streets and neighbourhoods of the city to alert residents to what had happened in University Square. They brought people out of their homes—buildings erected by Ceaușescu’s orders, of a hideous ugliness. So ugly that even today’s most wretched constructions look as though they were designed by Michelangelo and built by Leonardo da Vinci. In factories and plants, night-shift workers stopped working and went out into the yards. They were joined by those about to begin the day shift. Together, they set off in columns toward the city centre. The route was well known, followed countless times before for demonstrations and parades held in honour of the Dictator (a story told in Communist Hell: the Cult of Adulation). This time, however, they were no longer “volunteers”—that is, forced to attend under threat of severe punishment. This time, they went of their own free will. With determination. With hatred for Ceaușescu and his communist regime. So that the deaths of so many young people only hours earlier would not remain without consequence. So that the Revolution that began in Timișoara and continued in University Square would triumph here, in Bucharest.

The Triumph of the Revolution

The regime’s forces, the shielded police supported by the army, blocked access to the city centre. After more than an hour of tense face-to-face standoffs, the soldiers gave in. Harassed, mistreated, and humiliated from the very start of their military service, they ultimately joined the demonstrators. They fraternized with the people, turning their weapons against the Dictator. The crowd, ecstatic, began shouting: “The Army is with us!” Together, they marched toward the Presidential Palace, the seat of the Communist Party Central Committee, and the epicentre of power. Ceaușescu was right there, attempting one last address to the crowd. Hooted and jeered, he was forced to flee by helicopter with his wife. Abandoned after a flight of just a few dozen kilometres, they wandered for several hours before being captured that evening. It was the end of his regime: the Revolution had triumphed. Romania was free from the Tyrant.

Epilogue and the Beginning of Conflict

December 22, 1989, at noon: Ceaușescu had fled, his regime had collapsed, and the Revolution had triumphed. But the victory was immediately followed by another struggle — Ion Iliescu’s coup d’état. Supported by Moscow, this ensured his hold on power until 1996. The Russians launched a “hybrid” war against Romania: disinformation, manipulation, and electronic attacks, all designed to guarantee the success of the coup. We, Angelo and George, were direct witnesses and participants in these tumultuous events. Their story continues in the next episode.

Comments